The Plastic and Metal World of Paco Rabanne

Originally published on Heroine, September 2019. Sadly Heroine.com closed down in 2021.

Earrings from Paco Rabanne’s first accessories collection—brightly colored plastic geometric large enough to offset the highly teased hair. Photo by Bert Stern for Vogue, May 1966.

The traditional definition of clothing—that it was made from fabric or pelts—was turned on its head by Paco Rabanne and his first haute couture collection, “Twelve Unwearable Dresses in Contemporary Materials”, shown in Paris in 1966. Instigating an interest in new materials and techniques, as well as influencing generations of designers, in the course of one collection Paco Rabanne changed fashion history.

A model wearing a plastic disc dress in his first collection, February 1966.

The Basque Francisco Rabaneda Cuervo was born into the haute couture. His mother was the chief seamstress at Eisa, Cristóbal Balenciaga’s first couture house in San Sebastian, Spain. A fellow Basque, Balenciaga moved Rabanne’s family to Paris in 1937 when he opened Balenciaga there following the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War. Raised in Paris, Rabanne went on to study architecture at l'École Nationale des Beaux-Arts in the mid-1950s. While there he earned money doing fashion sketches for Dior and Givenchy and shoe sketches for Charles Jourdan, yet he went on to take a job with August Peret, France’s foremost developer of reinforced concrete, where he worked for over ten years. Enamored with fashion, he looked for ways to incorporate his architectural and engineering training with clothing. By the early 1960s he was designing on the side for couture houses—a beaded cage-look at Givenchy, embroidered dresses at Nina Ricci—when he met young, up-and-coming Parisian boutique designers Emmanuelle Khanh, Christiane Bailly, and Michele Rosier. Starting in 1962, Rabanne began designing plastic accessories for them that sold incredibly well in Parisian boutiques and caught the eyes of American department stores. Of them, Rabanne said in 1965: “They came like three bombs into fashion—full of new ideas, madly imaginative. At least, they gave a shock, excitement to dull, conventional rtw. They reflect the young modern spirit in fashion, not to serious. They dare and I like that… Fashion is fun and we understand that.” While still creating their accessories and designing beaded cage-look items for couture houses, he launched his own accessories line for spring 1966 with a range of vividly colored plastic pieces in geometric shapes.

Donyale Luna modeling a pink, silver and green plastic disc dress in Vogue, April 1966. Photo by Guy Bourdin.

By February 1966 Rabanne was ready to show his first complete plastique collection. Entitled “Twelve Unwearable Dresses in Contemporary Materials,” it consisted of “evening dresses, bathing suits, jewelry, belts, sunglasses, purses, headgear—all light, supple, mobile, plastic discs arranged in spectacular forms: cubes, spirals, circles; all startling colors: hot oranges, reds, golds, silvers.” The fashion press was captivated, saying: “Gone are the century-old threads and needles, replaced by a work table covered with pliers, wire, punch hole machines, and cutout dies. Many feel this may be the biggest fashion news in a generation.” Though these first dresses were made as experiments to show what could be done with plastic—punching holes into rhodoid plastic discs and using wire rings to hold together in a modern take on medieval armor—they were immediately ordered by all the most important trend-setting stores in the United States, where they sold for $300 and up special order. Shown over body stockings, the dresses were for dancing (sitting was not recommended)—and all came with extra discs and wire rings in case of any damage.

Paco attributed his immediate success to their newness: “My dresses are successful because they are shocking. It’s impossible for a woman to wear one and not by noticed.” He went on to say that, “I thought a woman working all day in flat-heeled shoes and sensible suits needed to recapture her mystery and femininity in the evening. It was up to me to supply her with a sort of second skin—rustling, iridescent, phosphorescent, soft yet sharp, supple yet rigid, transparent yet opaque.” Rarely does a designer’s work cross over so quickly into the slipstream of popular culture as Rabanne’s did. Appearing on famous singers and celebrities, on television backup dancers, in movies (he made some plastic dresses for Casino Royale and Audrey Hepburn in Two for the Road), and inspiring Jane Fonda’s iconic costumes in Barbarella, Paco Rabanne was ubiquitous from 1966 to 1970—copied by designers, mass-market manufacturers and teen magazines who provided instructions on how to “make your own.”

Paco Rabanne also brought plastic to the beach with this bra top, micro-mini skirt and headpiece. Photo by Hiro for Harper’s Bazaar, June 1966.

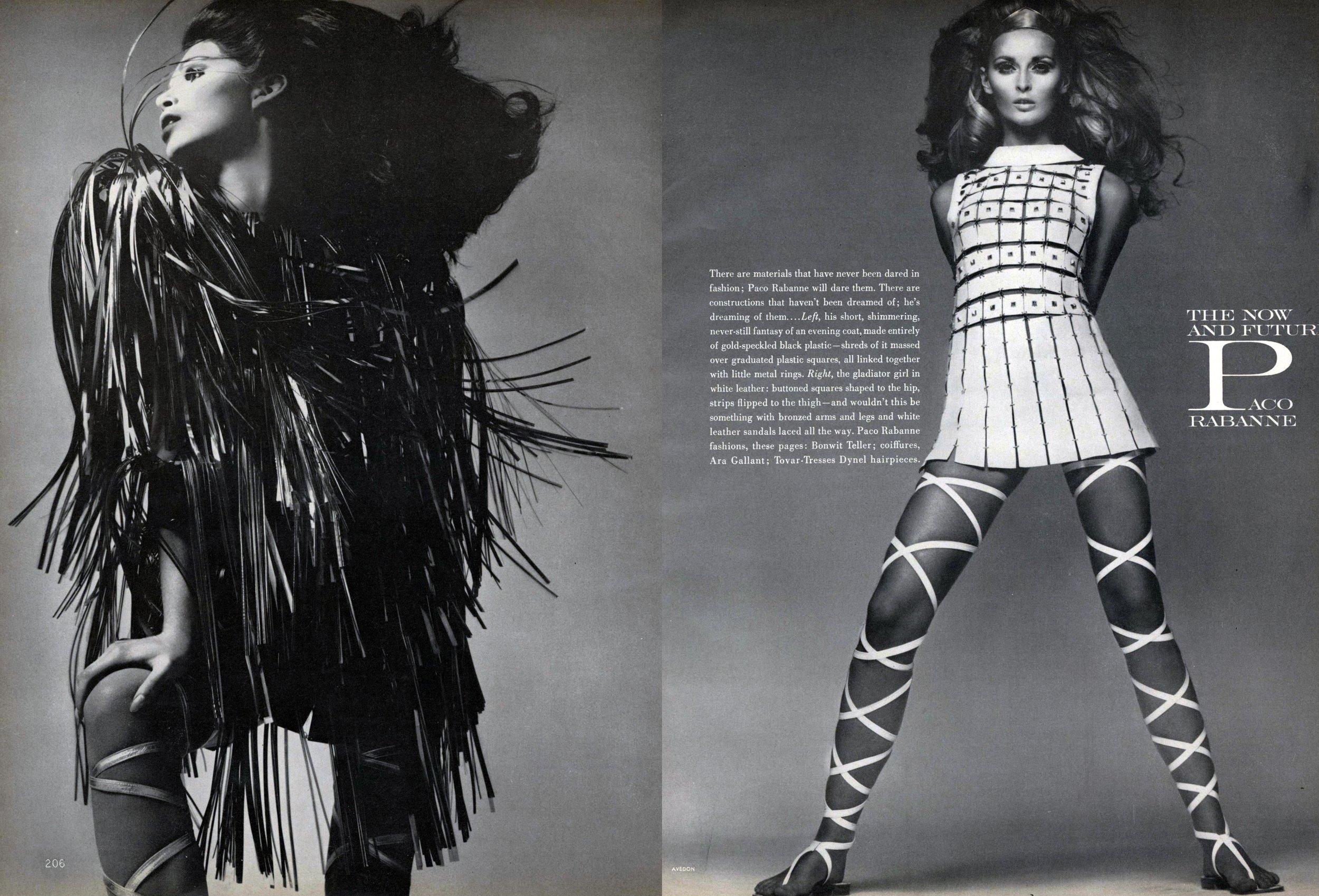

As Vogue said of him, “There are materials that have never been dared in fashion; Paco Rabanne will dare them. There are constructions that haven’t been dreamed of; he’s dreaming of them…” For all his forward thinking modernity there was a definite historicism to a lot of his work, especially once he started working in metal and leather. At his next collection in July 1966 he added in dresses and coats made from leather pieced with rings, as well as his first pieces using aluminum discs and triangles—all what he called “the Armor Look.” The fresh flower-petal shades of his revolutionary plastic designs took on a darker, harder feel in shining silver and brown leather. Women’s Wear Daily remarked of his July 1967 collection that, “While most of Paris is thinking pretty, Paco Rabanne still leads the violent set. His models come out like Valkyries… Even the little girls look like miniature citizens of Sparta.” Medieval chainmail, Valkyries, Spartan warriors—there was little of the bright newness that first captivated the media only a year and a half before. Affordable paper dresses, made from sheets glued or taped together, were a welcome respite from his warrior ladies, as was colorful chainmail fashioned into micro-mini slip dresses in 1968.

For Rabanne each season was an opportunity for new experimentation, such as the raincoats molded from a single piece of plastic he introduced in 1970. Paco officially joined the Chambre Syndicale de la Haute Couture in 1971, showing a more “chaste and sophisticated” version of his designs—replacing heavy hardware with fine metal mesh and fabrics like jersey and velvet. Rabanne took to layering mesh slips and bras over slinky black evening gowns and also introduced patchwork denim and crocheted leather designs, which were all quite a shift from a man that had previously sought to erase the needle and thread.

Paco Rabanne’s warrior princess, reminiscent of medieval armor. Photo by Irving Penn for Vogue Italia, January 1968.

Marking the beginning of a new era, in 1969 he introduced his first perfume Calandre, named after the metal grill on the front of a car—the scent was meant to smell like his all black boutique filled with metal scaffolding and chairs made from leather sports car seats. Hugely popular, Calandre set the stage for two decades of incredible sales for Paco Rabanne’s scents and toiletries—and very little interest in his clothes. With his name and fashions so clearly evoking the 1960s, they fell out of fashion completely. Known more for his many licensing deals and the often-crackpot theories he spouted to the press, Paco gained the nickname “Wacko Paco” and published several New Age books including one predicting that the Soviet Mir space station would crash into Paris and destroy it in 1999. The same year that failed to happen Paco Rabanne retired from fashion design (he’s still alive but remains very distant from his eponymous business).

With a fashion house so deeply aligned with an era (the late 1960s) and with a specific aesthetic (futuristic warrior), there have been difficulties updating the house and finding its relevancy today. A number of designers tried their hand at it, but since 2013 Julien Dossena has been working to find a contemporary understanding of Paco Rabanne, creating designs that “are about giving back the strength of Paco Rabanne’s work but also exerting my voice.” His spring and fall 2019 collections have been particularly acclaimed for the way he has taken Rabanne signatures, like chainmail, and integrated them into broader collections that incorporate a number of different styles and elements. A blend of now, the future and the past—a design philosophy that Paco Rabanne himself could easily have espoused.

A spread by Richard Avedon showing Rabanne’s remarkably modern aluminum and plastic dresses and coats. Vogue, March 1967.

Françoise Hardy modeling the most expensive dress Paco Rabanne ever made, all gold and diamonds. Photo by Jean Louis Guégan, 1967.

Paco Rabanne fitting two actresses in his costumes for the film Casino Royale, 1967.

A spread by Richard Avedon showing Rabanne’s remarkably modern aluminum and plastic dresses and coats. Vogue, March 1967.

Pieced leather and metal in Paco Rabanne’s fall/winter 1967 collection.

Brigitte Bardot in a striped chainmail mini dress and headdress. Photo by David Bailey for Paris Match, 1968.